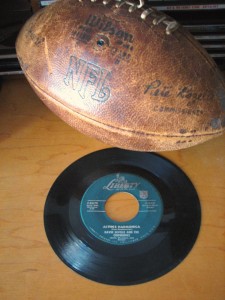

Like my fathers’ mother, like my father, I love my stuff. I’m no Collyer brother. My place is neat, in its own way. I still own my first two records, both by Dave Seville and the Chipmunks: “Witch Doctor,” in 1958, and 1959, “Alvin’s Harmonica.” The football is from 1969 and the main reason it’s still here: I religiously duct taped it like a car accident victim. When I had no duct tape I used electric tape, this pissed Dad off, since most wires in our apartment and my grandmother’s apartment were frayed and Dad kept a roll in his pocket on the weekend.

After 40 years of flying over and bouncing along concrete and asphalt, my friend, “Herman,” the football stands by my side.

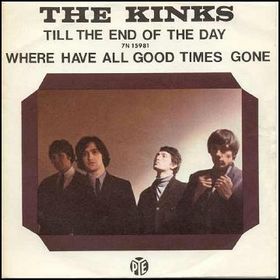

I was talking with a friend about how much I love Ray Davies and the Kinks music. This reminded me of a frigid November Saturday afternoon in 1965 when I was eleven.

For some reason, I was staying over my Aunt Barbara’s apartment in Elmhurst. I liked to wander around the neighborhood by myself, so I was window shopping along Roosevelt under the El and Jackson Avenue. I had a buck, which meant today I would buy one 45 single, and it better be a good one. When I was eleven, no decision carried as much weight and thought as buying a record. There was a small music store near the Jackson movie house. I tired out the clerk looking over the new releases and finally decided on “Till the End of the Day,” by the Kinks, because I heard “Where Have All the Good Times Gone?” the flip side once and liked it fine. It was an unexpected gift buying a single when the B side was a good song too.

I ran a half mile to Barbara’s apartment on Macnish Street, not breathing, said hi, and went straight to the Victrola. Saw something disturbing.

“Barbara, why is the record player unplugged?”

“It’s broke.”

“Huh?”

OK now I was in hell. New music with no means of playing it. I dropped into a chair. Barbara saw the shape I was in and made a suggestion.

“Tommy, Joanie’s not home, but why don’t you go try Betty?”

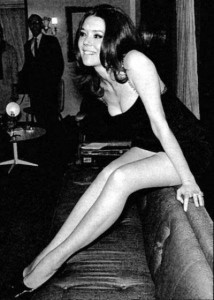

Barbara, my Aunt Joan, and their friend Betty Mulhern, all lived in the building. Betty Mulhern was Emma Peel, Barbara Feldon and Serena, Samantha’s evil cousin all rolled into one. If you didn’t like brunettes, and saw Betty, you’d like brunettes. She danced every new dance, and her wild hair flew. She wore tight shorts on long legs, she wore clam diggers, and she painted her pretty toes. Her eyes sparkled, her nose twitched. I couldn’t make eye contact with her without my belly feeling funny.

I went down the hall and knocked on Betty’s door. Music was playing.

“Hey Tommy, what’s up?”

“Hmmm, I have a new record, Barbara’s player is broken. Can I play it on yours?”

“Sure, come in.”

I put it on. Betty was doing the dishes, and she started to sway her hips. All I could do was watch her move back and forth, back and forth.

I played both sides five times. Would have made it six, if Barbara didn’t come in to retrieve me.