In the bustle of New York City, tucked away in the charming neighborhood North of Little Italy (Nolita), nestled between the posh boutiques beneath the trees outstretching their limbs over Elizabeth Street is a neat, little storefront with a large sign declaring “Moe’s Meat Market.”

Years ago, Moe’s had been a meat market. In fact, the grandson of the original owner still operates another meat market across the street. However, for the past 30 years, this site has been the studio and gallery for the art of Robert Kobayashi, or Kobi as he is known by his family and friends.

Through his career, Kobi’s art has flourished through a variety of media while he has worked in a broad range of techniques. Beginning as an Abstract Expressionist, he moved into Surrealism, then into Pointillism. After moving to Little Italy in the late 70’s, he also began to work with tin.

While quietly and prolifically producing his art, Kobi has enjoyed a number of successes. The New Yorker and The New York Times, among numerous other publications, have featured articles on him. His works have been placed in the  permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art, the Brooklyn Museum, Honolulu Museum of Art, the Microsoft Art Collection, in addition to a number of private collections.

permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art, the Brooklyn Museum, Honolulu Museum of Art, the Microsoft Art Collection, in addition to a number of private collections.

In 1925, Kobi was born in what was then the U.S. territory of Hawaii to parents of Japanese descent. At a young age, he discovered his artistic interest by drawing cartoons. Then after serving in the U.S. Army in the mid-40’s, he attended The Honolulu School of Art where he studied under Wilson Stamper. Kobi’s talent was immediately recognized as he was awarded the Jon and Eleanor Freitas Prize in 1948.

Kobi’s older sister, Fumi, had encouraged his artistic development from an early age. A promising intellectual herself, Fumi attended Barnard College in New York City and Kobi enrolled at the Brooklyn Museum Art School with the support of the G.I. Bill. When Fumi moved to Paris, Kobi visited. Although he only stayed in Paris a few months, the city made a profound impression on him. Fumi tried to arrange a residence for him at the L’Atelier de Fernand Leger, but Kobi decided to pursue his interests more independently and befriended a number of Japanese artists who were working at various museums in Paris.

Returning to New York City, Kobi was eventually hired by the Museum of Modern Art and tended the ‘Japanese House’ which was reinstalled in the museum’s garden in 1954. Incidentally, while working in the warehouse one day, he met Kate Keller, the lady he would later marry. Kate, also employed by the museum, would eventually reach the position of Head of the Fine Arts Photography as she maintained the photo imaging studio. Through her career, she worked on numerous projects such as documenting the disassembly of Picasso’s Guernica exhibit and assisting Billy Kluver with his publication: A Day with Picasso, Twenty-Four Photographs by Jean Cocteau.

For over 20 years, Kobi’s residence would alternate between Hawaii and New York. Then in 1977, he purchased a small building at 237 Elizabeth Street where the signage of Moe’s Meat Market remains, but where the artist, his work and his family now reside. Before becoming a trendy neighborhood, the area was in a state of neglected disrepair. Through the years, Kobi and Kate diligently renovated this weary structure into the cheerful and quaint building that now serves as a cozy home, studio and gallery.

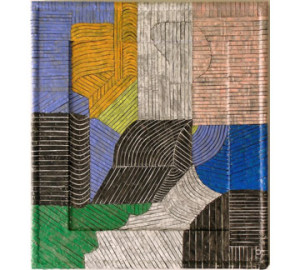

The revival of the building on Elizabeth Street, and subsequently the entire neighborhood of Little Italy, parallels a manner of expression in Kobi’s art. For years, Kobi would transform tin containers into carefully crafted sculptures. Through a lengthy and tedious process, he would select the tins by their patterns and designs to accentuate the work of art that they would compose. Then he would meticulously cut the tin into pieces and attach them to wood forms he would construct. The works are a combination of his inner vision and the resources he had at his immediate disposal. They are constructed as much from him as from the city in which he lives. Through this, just as the building he bought, he revitalized the abandoned into what became touching and comforting.

Despite the coldness one would expect from the medium of tin, Kobi’s work subtly suggests a gentle wit and a delicate touch. The rigid nature of the metal is softened into a suppleness of shape and color. The chill warms with the nimble diligence of his fingers guided with the expressiveness of his affectionate mind.

The sculptures of flowers stand in vases just as floral memories of Hawaii stand within the urban compartments of Manhattan. Through this, they display the dual realities of everyone’s life whether balancing the familial with the professional, one’s interests with one’s obligations, or any number of the day and night antipodes of our existence.

Also, within these flowers there is the charm in the uniqueness of each bloom gesturing with personality. A heavy bud droops as if weary in its struggle to bloom. Open flowers boisterously nudge one another to parade their petals. Or a moon flower sits alone in a window sill to reflect the solitary lunar face in the chilly night sky.

In the 80’s, as buildings in the neighborhood were being renovated, Kobi began to salvage the hammered tin ceilings and use them for two dimensional pieces. This brought a new element to his work that had been abscent for most of his career: frames. Through the 50’s when Kobi was working exclusively with paint, his pieces seldom had the luxury of being placed in frames for display. Instead, he would often store them on the grounds at MoMA where he worked. On a few fortunate occasions, generous individuals provided him with storage space. During his surrealist period, he painted on small boxes he built and which he would offer to his friends as gifts.

With the two dimensional tin pieces, the frames became integrated into the works. They do not present the work, they are intrinsic to the expression. Kobi is defined as much by his childhood in Hawaii and his home in Nolita. The locations are not frames for his life, they are essential parts of his being. As Kobi taps the tin into the shape of his vision, his art spills over the frames. And in his most recent and untitled piece, the lavender blooms of the irises rise from the beauty from within and overgrowing their humble beginning, extend out over the frame as if to touch the entirety of life, a life endlessly renewed as it renews.

With the two dimensional tin pieces, the frames became integrated into the works. They do not present the work, they are intrinsic to the expression. Kobi is defined as much by his childhood in Hawaii and his home in Nolita. The locations are not frames for his life, they are essential parts of his being. As Kobi taps the tin into the shape of his vision, his art spills over the frames. And in his most recent and untitled piece, the lavender blooms of the irises rise from the beauty from within and overgrowing their humble beginning, extend out over the frame as if to touch the entirety of life, a life endlessly renewed as it renews.

For more information about Robert Kobayashi’s work: Kobi

Garrett Buhl Robinson is a poet and novelist living in New York City. www.garrettrobinson.us